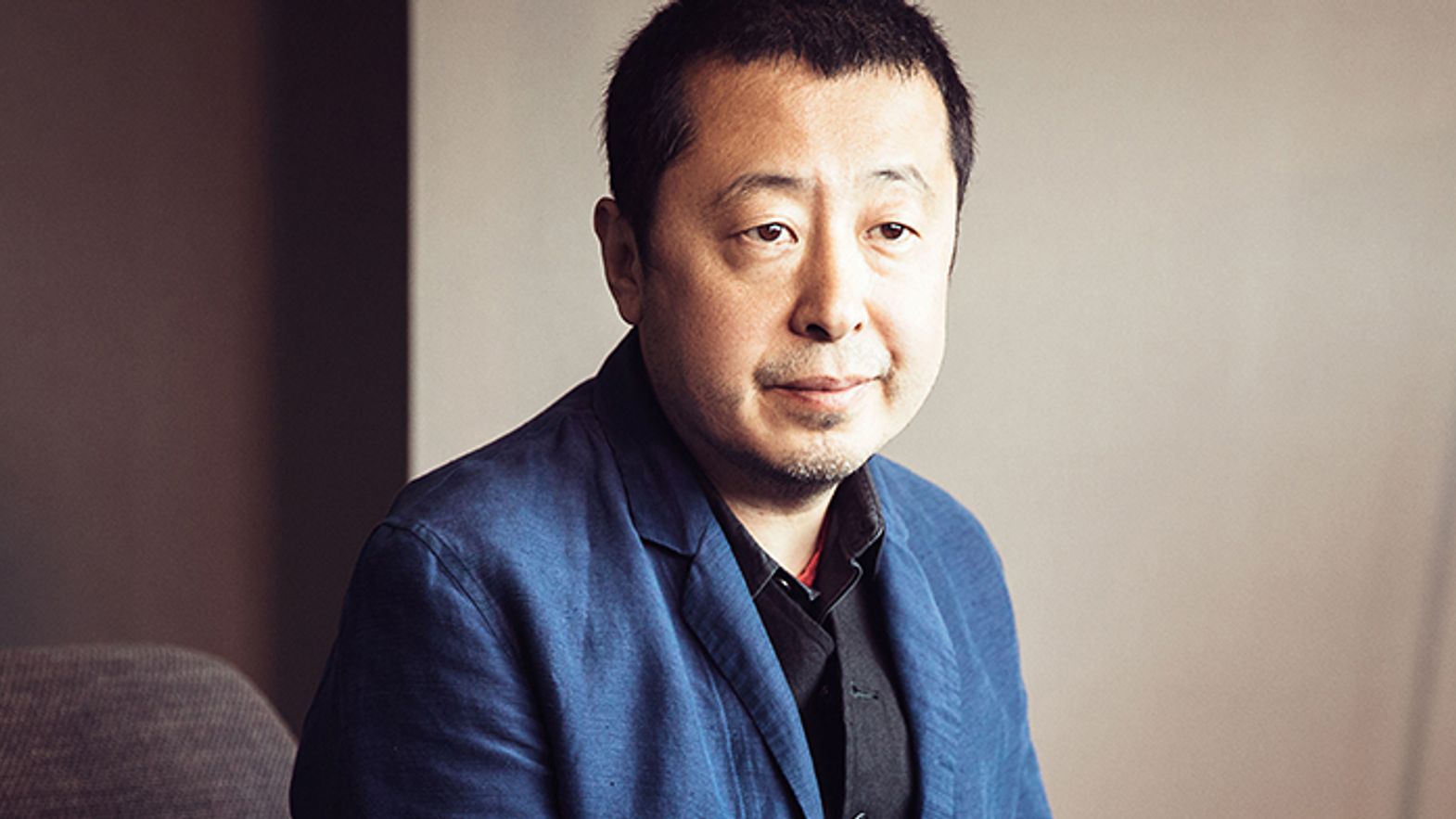

Alongside directing some of the most vital Chinese films of recent memory (including A Touch of Sin, The World, Platform, Still Life and many more), Jia Zhang-ke is also a teacher at a Shanghai film school. As such, the director was happy to take some time out of his schedule as the President of this year’s Concorso internazionale Jury to speak to this year’s Filmmakers Academy class at Locarno, alongside members of the Critics and Industry Academies.

Moderated by Stefano Knuchel, Head of Locarno Filmmakers Academy, the talk began with Knuchel recalling the decision in 2010 to award Jia with a Lifetime Achievement prize. Denouncing the perceived notion that Lifetime Achievement implies the end of career (Jia’s first feature was only released in 1998), Knuchel clarified that Lifetime Achievement in fact refers to when you have achieved something worthy of accolades. He says there was a feeling at that time, when Jia’s last released film would have been 24 City, that the filmmaker had “documented the evolution of China in a very specific way”.

This conversation starter, more a comment than a question, led to Jia, via translator, delving into a nearly 50-minute monologue about his career to date, touching on his earliest days behind the camera to the trouble recent films like A Touch of Sin have had with getting screened in his home country. Much of this biographical material can be found through other resources, including Walter Salles’ 2014 documentary about the director, but the discussion still proved compelling in having the man himself articulate his various motivations in audible form to an assortment of budding young filmmakers.

First of all, though, regarding that Locarno award in 2010, he says, “I was told I would be awarded a so-called Lifetime Achievement award. I was very astonished. Oh my god, is it an end to my career? And then my wife told me, you’d better not go and get this award because it could be bad luck.”

On his early beginnings, he says, “At the beginning I just loved filming things. I didn’t have that much experience. I came to study in Beijing in 1993. I was 23 then. It was also a moment when China was changing rapidly. I came from a very small town called Fenyang. It has several hundred years history from the Ming Dynasty. In 1997, that small town had to be rebuilt again. When I went back to my home during the spring festival, my father told me, ‘You need to take a very close look at the city or it will be gone very, very soon.’ So, I was very upset then because looking at the buildings and the spaces, I though it’s going to be vanishing very soon. Those vehicles and those buildings are the vehicles of my memories. Making film is a way to keep your own memories and a way to revive memories.

“I began to make films about both changes in society and also changes in the people,” he continues. “I want to make films about the realities of the personal status of the people during a period of time. Back then in China, lots of films were out of reality because a lot of films were made by government or state-owned studios. Myself and my friends at the time wanted to make independent films to record the reality of China back then [at the start of his career].”

Regarding revisiting the past through film, Jia says that “forms of art like writing and filmmaking are all the same because they’re all depending on the current experience we have in our imagination with the past. And then we always use our experiences to create the details in life. We’re always missing the details in the past because we’re not living in the past. But that is the most powerful part of art because through the art, like filmmaking, we can always use our vision as a way to make the details and also to reflect our imaginations. As a filmmaker, no matter the subject we are filming – the present, the past or the future – we are the people that recall history, or create history, because all those images you are making will become the images of the memories that recall the lost and found, that recall information. Today, you are filming the time of the present, but that will become history very soon. And even your filming of [something set in] the past will become history, too. We are all people recording history.”

As a final piece of advice for young filmmakers in his monologue, Jia instructs that “you have to be sincere or loyal to your own feelings, to your personal emotions, but, also, as a human being, you are living in a society, so you have to echo the perspectives of the society. You have to have multiple perspectives in order for you to become more open, to have different thoughts on the topics you are talking about.”