©Locarno Film Festival

©Locarno Film Festival

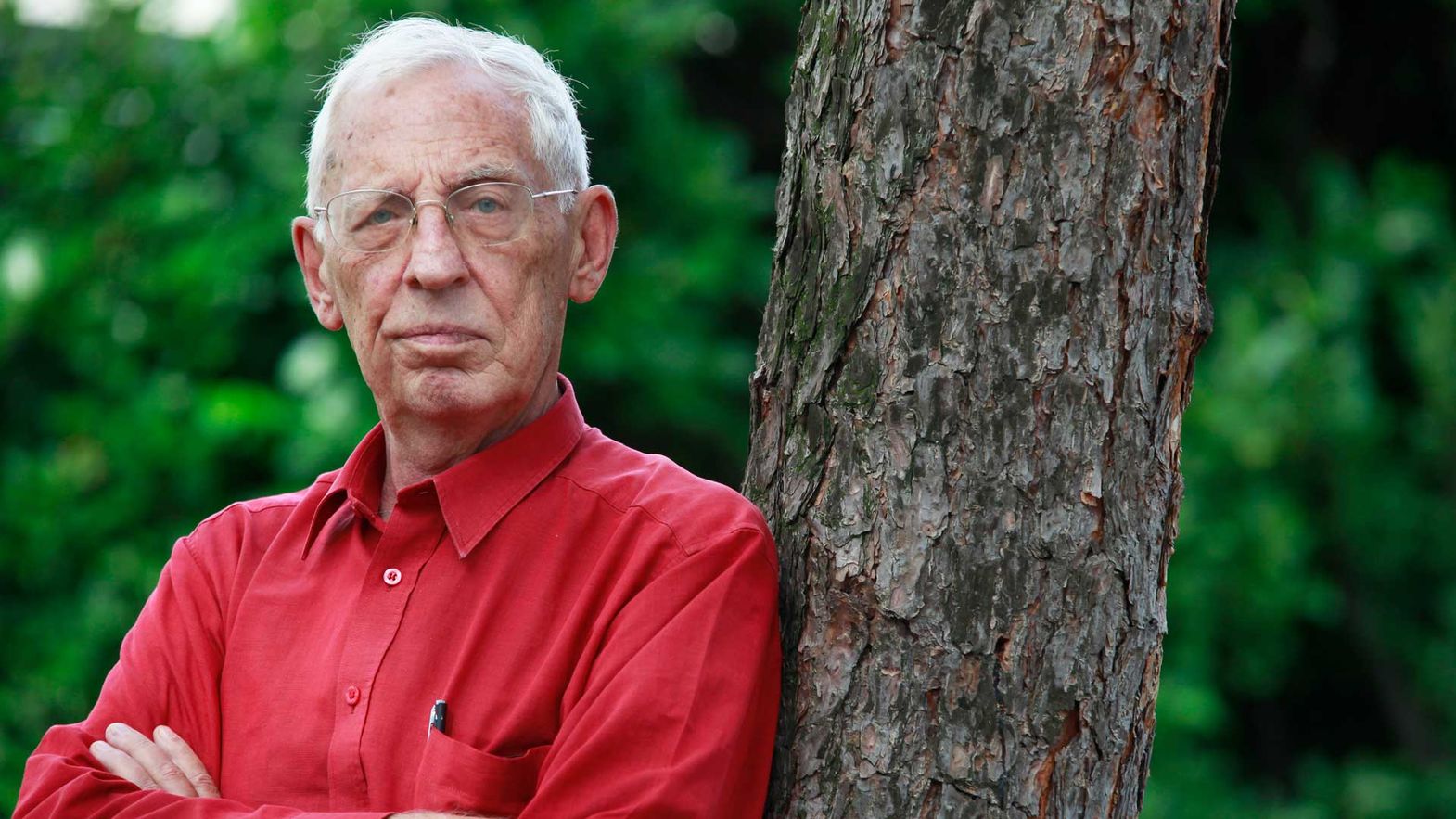

Not only a film critic, not only a historian – among the greatest in international cinema – Adriano Aprà belonged to a rather exclusive group of thinkers: those who made things happen. He founded magazines (at 26, Cinema&Film), breaking critical taboos – with a mission “not to repeat that which is already solved but to verify collective research in progress”. He ran ciné clubs (the legendary Filmstudio in Rome) leaving doors open to contamination and influence from the avant-garde. He directed important festivals (the Salso Film & TV from 1977 to 1989, the Mostra Internazionale del Nuovo Cinema in Pesaro from 1990 to 1998), organized memorable retrospectives for others (notably, Kenji Mizoguchi, Howard Hawks, Joseph L. Mankiewicz for the Venice Film Festival), and led the Cineteca Nazionale from 1998 to 2002. Finally, he wrote always-unconventional books and taught cinema at the university. These are dates and occasions that do not, however, serve to define him. Cinema for Adriano Aprà was a country – borderless and timeless – that he inhabited with the curiosity of the nomad and the insatiable wonder of the explorer. Among those who mourn his passing today, many of us boast a specific moment when Adriano entered their life as a cinephile. Not necessarily inevitable moments, and therefore taken for granted (a first contact with Rossellini, Dreyer, American cinema...), but discoveries and rediscoveries that left a definite mark.

How can we forget, among many others, the invaluable little volume Neorealismo d’appendice - Per un dibattito sul cinema popolare: il caso Matarazzo (published by Guaraldi). This was a work that allowed so many to enter the world of a filmmaker – Raffaello Matarazzo – who was until then mistreated, to say the least, by “official” critics. As in that case, Adriano paid regular attention to cinema around the world that had been left in the shadows or been critically misinterpreted, all the better if it was linguistically and aesthetically “outside of the norm”: the very first contacts with Iranian cinema, the encounter with Palestinian resistance films, the New American Cinema of Jonas Mekas and the never-ending body of work of Stan Brakhage, the ‘newsreels’ of Robert Kramer and the Factory of Andy Warhol (there is his Il cinema di Andy Warhol, written with Enzo Ungari, Arcana Editrice).

The distinctive signature of Adriano’s critical thought was to flush out the modern and point to a cinema able to move forward, to gamble, to avoid getting mired in an artistic deadlock. Recall his early passion for Philippe Garrel, in particular in hosting an extraordinary screening of Elle a passé tant d'heures sous les sunlights (She Spent So Many Hours Under the Sun Lamps, 1985), and then for Jim Jarmusch or Chantal Akerman, his capability for fertile dialogues shared with the likes of Serge Daney, or even to interact as an older brother with critics younger than him, like the anomalous and brilliant Enzo Ungari and Marco Melani.

He was a Rosselliniano capable of fleecing the Rossellinians: an accomplice of Bernardo Bertolucci (Adriano appears in the Agonia episode of the 1969 collective film Amore e rabbia [Love and Anger] alongside Julian Beck and Judith Malina and fellow filmmaker Giulio Cesare Castello); a profound admirer of the cinema of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet (he is the protagonist, with his ascetic physiognomy and perfect French pronunciation, of Les yeux ne veulent pas en tout temps se fermer ou peut-être qu'un jour Rome se permettra de choisir à son tour [Othon, 1969]); close to the new Italian cinema born around ‘68, he collaborated among others with the painter and director Mario Schifano (in Satellite [1968] he is the person who announces Dreyer's death; in Umano non umano [1969] he invited us to intone “insulting songs and whisper sinister prophecies”).

Adriano Aprà – to use an image from Serge Daney – is a passeur. Someone who literally passed through the cinema of the last century, facing forward. He confirmed this himself, writing perhaps his last text only a couple of months ago (dated February 12, 2024 and published in Indian Nation).

That final word is a somber piece of writing in which he hints at the now irreversible catastrophes of the planet and in which we are enlightened only when Adriano Aprà speaks of the cinema of the future – an expanded, quantum, extraterrestrial cinema, capable of “leading us by the hand to unexplored shores.” It is the cinema of the unspeakable, of that which has rarely been dared; the type of cinema that cinephiles never tire of frequenting and coveting – united by an omnivorous but not blind passion. They are privileged spectators for whom Bazin’s quote, “qu'est-ce que le cinéma?”, is no longer enough; instead, they flee forward, trying to imagine not what the cinema is, but what it will be. Just like the kids in the last frames of Roma, città aperta (Rome, Open City, 1945) or the 12-year-old Jean-Pierre Léaud running toward the sea in the finale of Les quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows, 1959). Adriano is here.

Piero Spila

Giona A. Nazzaro – Artistic Director